Still Running After All These Years

The year was 1973 and my wife, Trina, and I had recently made an arduous cross-country move from south Florida to central California, our Oldsmobile Cutlass straining under the weight of the U-Haul trailer into which we had loaded a few sticks of furniture and a half-dozen orange crates crammed with books. Beginning a three-year Master of Divinity program at Berkeley’s Graduate Theological Union, I decided to pursue the running I had abandoned after my high school track-and-field days. There was a little-used quarter-mile cinder track just a few blocks from our apartment and, sporting a new pair of Adidas, I began running laps – a bit of a challenge since I was still a pack-a-day smoker.

That was fifty years ago. A few months into my new routine I kicked the cigarette habit and was soon averaging two to three miles in thrice weekly outings. Following graduation, I accepted a call to the Unitarian Church in Sioux City, Iowa and began exploring new running routes on the streets of a Missouri River city known for its slaughterhouses and malodorous rendering plants. Here I linked up with a handful of other runners, and that camaraderie motivated me to pick up my pace. At that point I was pounding the pavement for the usual reasons: fitness and emotional equilibrium. But I also found it enjoyable. As Larry Shapiro, a professor of philosophy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and also an avid runner, perceptively observed in Zen and the Art of Running:

Runners, for the most part, enjoy running. A few people may muddle through only to lose weight or gain other healthful benefits, I’ll go out on a limb and say that most runners love to run. They find relief from stress, take pride in goal achievements, and relish the simple pleasure that running affords them.

At the time, it never even occurred to me to enter a competitive “fun run” of any sort. But then we made another move, this time back south for advanced degree programs at Florida State University. Tallahassee was, I soon discovered, something of a regional running mecca, and after some prodding from a neighbor in our student housing complex I signed up for my first 5K road race. I had never bothered to time myself at this distance and had little sense of how I might finish. Crossing the line in just a shade over nineteen minutes I was flabbergasted – and I was also hooked.

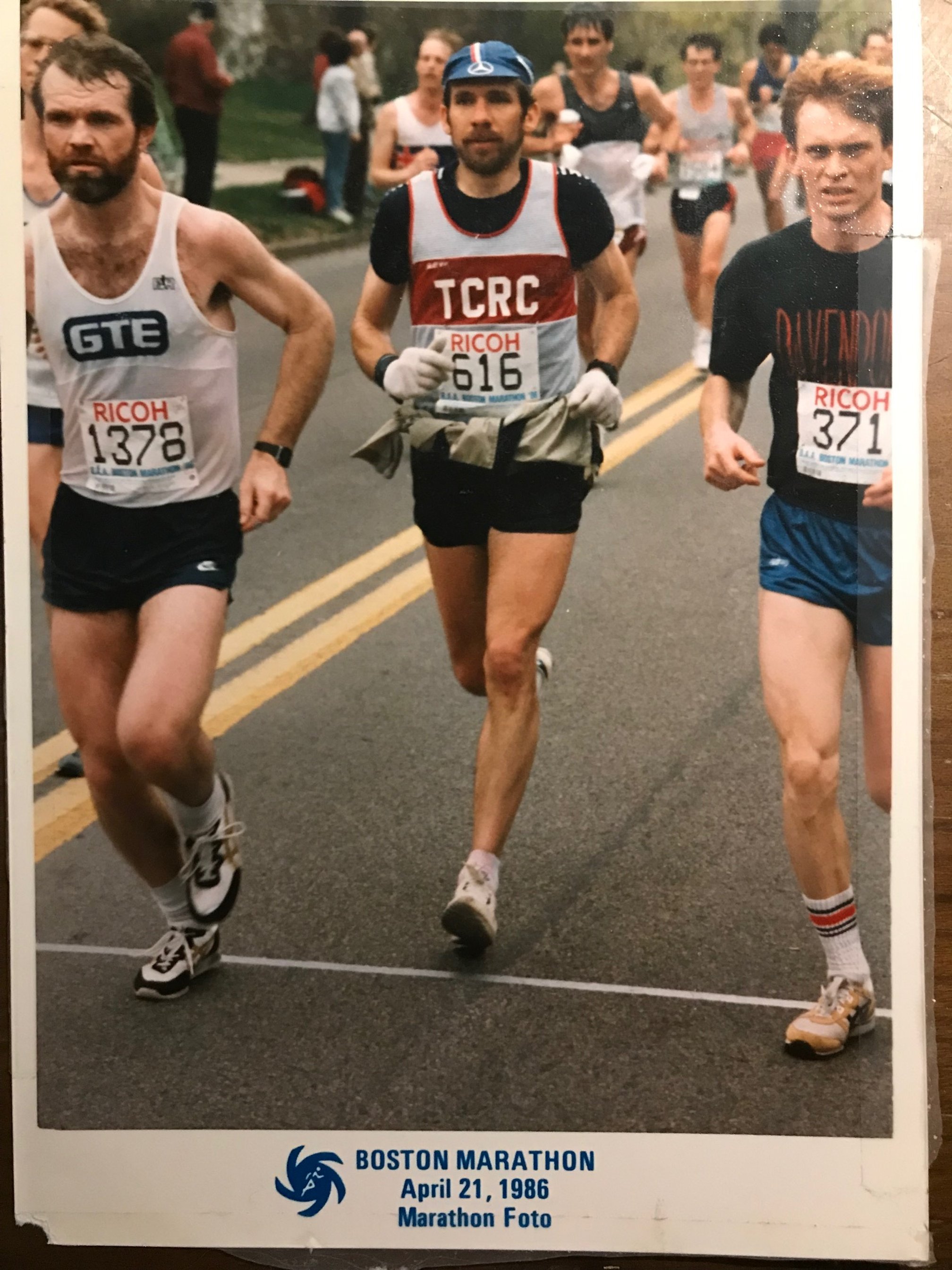

The author competing in his fifth and final Boston Marathon

In the years that followed, first in north Florida and later in Upstate New York, I competed in innumerable races, from the mile to the marathon. At the age of thirty-two I was logging 60-70 training miles a week, including interval sessions on the track, and was rewarded with sub-sixteen times in the 5K and a 2:36 PR for the grueling 26.2-mile distance. But by 1987 life changes demanded a shift of priorities. Running had never impinged on my professional duties or marital pleasures, but now a baby (Kyle) had entered the picture. Racing became a luxury, and preparing for marathons was just too time consuming (and depleting!). But running? That had become a permanent fixture in my weekly routine, a “positive addiction” as Dr. William Glasser once characterized it.

These days I run twice a week, usually for fifty to sixty minutes at approximately an eleven-minute pace. I stopped competing thirty years ago and, as in the beginning, my runs are solo affairs along the Lakeshore and down the crushed gravel path to Madison’s iconic Picnic Point. I am fortunate that over the course of these many decades I’ve only sustained a couple of injuries that required a pause in training: an achilles tendon strain a month before my first Boston Marathon, a pulled hamstring, and a fall a few years ago that messed up my ankle.

So what’s the formula that has kept me going? Perhaps my own experience will prove useful to those who aspire to run into and through their seventh decade. Admittedly, I am not a physiologist or a sports medicine clinician, but I think much of what I have to offer is just common sense.

I really didn’t have much choice with respect to the first piece of the puzzle. I am, in the runner’s lingo, what’s known as a “shuffler,” which simply means that I run with a short stride and minimal leg lift. To put it more elegantly, I glide rather than gallop. While this style of running doesn’t lend itself to sprinting, it’s quite efficient for tackling longer distances. And, because the legs aren’t subjected to as much pounding, there’s less wear-and-tear on knees, hips, and arches. For sustainable running, then, it might help to alter one’s stride and stay off the balls of the foot.

Then there’s the matter of shoes. During my competitive days, I rotated three or four pairs from different manufacturers. This meant that I wasn’t putting stress on the same muscles and connective tissue at every session. I also made a point to retire those shoes at the first sign of knee discomfort. While the outsole of a trainer might, on inspection, appear only slightly worn, the cushioned midsole has probably compacted. Today’s high-tech running shoes are good for no more than 300-500 miles. Quality footwear isn’t cheap. Even so, running is just about the least expensive form of aerobic exercise you will find – provided you stay injury-free.

One secret to avoiding bio-mechanical injury is to stay off the concrete as much as possible. Even the best footwear can’t stand up to repeated strikes on hard, unyielding surfaces. Macadam (blacktop) is better, unpaved trails better yet, and short turf (real or artificial) best of all if you want to go the distance. Fortunately, for the past thirty-five years I have lived in a community where runners could make such judicious choices.

Addicted or not, don’t put all your fitness eggs in one basket. Once a six-day a week runner, I’m now down to two or, on rare occasions, three days of hoofing it. We hear a lot about the benefits of cross-training, which becomes almost essential as we age (a collagen supplement is also helpful). My own regimen includes a long session of yoga and calisthenics, or an hour on the bike, when I’m not running. As a result, my overall fitness and muscle tone are much better than if I’d pursued only running.

Avoiding distractions is something else to consider. Over a half-century I’ve logged thousands of miles and never once felt drawn to earbuds. People seem to think that running is boring, just a matter of putting one foot in front of the other time and time again. I have never found it to be so. Find a comfortable rhythm, pay attention to sensory input, observe the subtle changes in the seasons and you might just run right into that natural “high” that experienced runners rave about.

Finally, it’s important to be realistic, especially as aging takes its inevitable toll on our performance. There are times I feel diminished by the fact that I can no longer break ten minutes for a mile. I look back in disbelief at that younger self who could maintain an under six-minute pace for twenty-six of them and wonder where it all went. But the thought passes, and I realize that I’m darned fortunate to still be running at all. Here’s Larry Shapiro again: “Aging runners measure themselves against their younger selves…and consequently see nothing but decline.”

(But Buddhism teaches) that there is no “I” who moves through time, because that would require that the ”I” be something permanent – something that remains unchanged as the rest of the world changes around it. The you now is not the same person as the you who existed then, so there is no you who is getting slower, or deteriorating, or declining…. It was that person, not you, who was capable of running six-minute miles.

This may not square with the way we ordinarily look at ourselves, but after a half-century in the runner’s world I think I can see the man’s point.