The Rest of the Story…

Michael Anthony Schuler was born on February 7, 1951, in Dixon, Illinois, the middle child of three. He spent fourteen of his first sixteen years on farms owned by his grandfather but operated by his parents who “learned by doing,” since neither had a background in agriculture.

Michael’s father, Charles William Schuler, grew up in Ronald Reagan’s home town of Dixon, attended St. John’s Military Academy, and served as an infantry officer in World War II. He married Zona shortly before being shipped overseas but the two divorced not long after his return to the states (not an unusual occurrence at the time). Charles studied business and literature at Kansas University, dreaming of becoming a novelist. His decision to till the soil was driven by necessity rather than choice, since his writerly aspirations went unfulfilled: his portrayal of a young military police officer serving in occupied Czechoslovakia didn’t catch on with the publishers. He did salvage the existentialist philosophy that he’d imbibed at KU, recommending it to his new wife, children and anyone else who showed the slightest interest in the subject.

Nancy Jean Balster hailed from St. Paul, Minnesota, where her father held a number of managerial positions in that city’s hotels, private clubs and as head of concessions at the busy St. Paul train depot. She attended Central High School, then earned a certificate in Occupational Therapy at Milwaukee Downer College. During and after the war she worked in several Veterans Administration hospitals, including one in Topeka, Kansas. It was here that she met and, following a brief courtship, married the debonair divorcee Charles Schuler.

For Michael, farm life felt isolating but he took more interest in the work than either of his siblings, William Eliot & Catherine Ann (both named after two of Charles William’s favorite writers). During his formative years Michael removed fences, tore down dilapidated sheds and chicken coops, raised hogs, fed a barnyard full of feral cats, ran an eighty-inch power mower, planted pine seedlings, harvested strawberries, and dug potatoes. Nevertheless, there was always ample time for hunting in the winter, fishing and swimming in the Rock River that bordered the farm during warmer weather.

School in Dixon was seven miles removed from the Schuler farm, and that meant a long, often painful daily bus ride to and from the classroom (painful because the driver required siblings to sit cheek-to-jowl on the hard, narrow seats). Michael was always an avid reader, and won ribbons for both the volume of his consumption and comprehension of the material. He acted in grade school plays, and as an eighth grader starred as Scrooge in the class production of Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol.” Michael continued with theater in high school, winning a minor role as a member of the Jets in “Westside Story” and the lead character (Mr. Dadier) in “Blackboard Jungle”.

Although not athletically gifted, Michael joined both the football and wrestling teams as a high school freshman. He was too small and too slow to make the cut in football, but he did enjoy some success as a middle-weight wrestler. After the family had sold the farm and relocated to Naples, Florida, Michael took up surfing, at which he became reasonably proficient. There was no indication at this point that twelve years later he would excel as a distance runner.

Naples High was academically a step or two behind the school Michael had left in Dixon, so studying took a back seat to surfing, working at his parents’ Holiday Inn (purchased using the proceeds from sale of the Dixon farm), and spending time with a girl he had encountered in an Algebra II class. He and Trina became an “item” as they say, and six years later exchanged wedding vows in a small sunset ceremony overlooking the Gulf of Mexico.

Naples was an idyllic sub-tropical town in the late 1960’s, but the living was perhaps a bit too easy. The crystalline white sand beaches and azure water were always inviting, alcohol and pot were easy to procure, restraints (legal or otherwise) on young, rambunctious white boys were few and loose. Still, Michael’s name regularly appeared on the school’s honor role, he was among the first members of the newly established National Honor Society, and twice was named “Student of the Month.”

His guidance counselor urged Michael to apply to prestigious schools in the Northeast, but he chose instead the recently established (1959) Florida Presbyterian College (now Eckerd College) just up the road in St. Petersburg. Situated on Boca Ciega Bay, it was just a mile from the Gulf beaches with their potential for further surfing adventures. FPC was more challenging academically than Michael expected, and since he had gotten out of the habit of studying he survived his freshman year by the skin of his teeth. Chastened by this setback, Michael put his nose to the grindstone and ended his undergraduate career with a distinguished overall average and a degree in political science.

Although social science was his primary focus Michael had also opted for courses in philosophy, religion, literature, ancient history, and anthropology. Moreover, at FPC/Eckerd all students were required to take two years worth of classes in the interdisciplinary “CORE” curriculum which exposed learners to subjects they might not otherwise find attractive. But Michael loved the diversity he found in these offerings, which presaged his later decision to pursue an interdisciplinary Ph.d. In the Humanities.

Having been accepted to two law schools, Michael elected instead to attend Starr King School for Religious Leadership (Unitarian Universalist) and prepare for a career in the ministry. This was a source of surprise and disappointment both to his major professors, and to his parents. Michael’s decision grew out of a growing fascination with religion and in particular its mystical aspect; he had recently begun a Zen-informed practice of meditation based on his reading of D.T. Suzuki, Allan Watts, and others. His choice of a UU seminary was natural: he had attended a small lay-led fellowship as a pre-teen and appreciated its individualist orientation and progressive, inter-religious flavor. Having been raised in a non-Christian, skeptical household, any other denomination would have been out of the question.

Trina and Michael had planned their wedding for July 3, 1973, but her younger brother died in a tragic accident shortly before the ceremony took place. The low-key event - attended by only a few family members - took place instead on August 27, two days before the couple departed for Berkeley, California and seminary. It was a solemn leave-taking since Trina’s parents were still in a state of shock and grief.

Starr King was one of a number of schools affiliated with the Graduate Theological Union, and was regarded by its peer institutions as a bit flakey. Scholarship wasn’t a priority so much as community bonding and practical skill-building. Michael ended up doing most of his coursework through other schools in the GTU network: systematic theology with the Episcopalians; Biblical studies with the Jesuits and Franciscans; Reformation courses with the Presbyterians; Jewish mysticism with the Center for Judaic Studies. He also deepened his practice of meditation at the Nyingma Institute, a Tibetan Buddhist school and monastery in the Berkeley hills presided over by Rinpoche Tarthang Turku.

Financing three years of graduate study without parental support proved challenging. Michael’s savings were practically exhausted when Trina landed a job in a sheltered workshop in nearby Richmond. Here she was able to make good use of her training as a special education teacher and counselor. Michael also brought in a small income from his work-study assignment with the Berkeley-based UU Migrant Ministry. Designated “Director of Communications,” he prepared promotional materials in support of California’s field workers and the United Farm Workers Union, led by Cesar Chavez. Although he was advised to stretch his M.Div. Program to four years (as many fellow students did), Michael finished in three and was duly ordained by the First Unitarian Church of Berkeley in June, 1976. He was twenty-five years old. Shortly thereafter, he and Trina packed up their Grove Street apartment, bought a few pieces of unfinished oak furniture, and drove to Sioux City, Iowa where Michael had accepted a call to the century-old Unitarian church.

That ministry lasted less than three years, and although the congregation grew by fifty percent, the shift from progressive Berkeley proved a shock to Michael and Trina’s system. Sioux City was a cow-town, crowded with 18-wheelers, slaughter houses, and rendering plants whose fetid emissions proved inescapable except when the wind blew from the north. Moreover, the small congregation’s established leadership didn’t see eye-to-eye with their young minister who brought with him big plans for “improvement.” Some of those plans were, in fact, implemented, but Michael and Trina threw in the towel after two and a half years, and left for Tallahassee, Florida, in mid-winter. Both had been accepted into Florida State University graduate programs for the upcoming Spring quarter. They soon settled into University housing with the two half moon parrots they’d adopted in Berkeley. Alumni Village was an international community, and Michael and Trina lived two doors down from a young Iranian couple and their children. Unfortunately, a budding friendship (Trina was busy helping the wife and mother with her English grammar) ended up on the rocks when the 1978 Iranian Hostage Crisis blew a hole in U.S. and Iranian relations.

On the whole, however, Michael and Trina’s two and a half years in Tallahassee provided a welcome respite. Trina excelled in her Master’s program, and Michael landed a position as a teaching assistant with full responsibility for undergraduate classes in the humanities. Although Eckerd didn’t boast a chapter of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society, at Florida State Michael did gain admission to the graduate honor society, Phi Kappa Phi. He had begun running in Berkeley and increased his commitment in Sioux City. Now he tested his speed potential at area road races and discovered that he actually had some potential as a distance runner. This became a source of camaraderie as well as personal pride, as the running community proved to be warm and welcoming. In the years that followed, Michael won multiple age-group awards in races from five kilometers to the marathon.

He was in the process of writing his doctoral dissertation when Michael and Trina moved to Binghamton, NY, to begin a new ministry. Given that the market for interdisciplinary humanities professors was rather limited (and paid poorly), it seemed only prudent to give the religious life another shot. This proved to be a formative and instructive experience. Michael had arrived in Binghamton unsure whether he really was “called” to the ministry and he questioned whether he was temperamentally suited for it. Now, he found himself in a situation that didn’t bode at all well for his professional future. Unbeknownst to him, the congregation had suffered a disastrous split two years before, which precipitated a financial crisis (Michael’s very first paycheck was returned for insufficient funds). Although a skillful interim minister had reunited the two warring factions, they barely tolerated each other. Moreover, each sought to bring the new minister and his wife into their orbit - a recipe for disaster. The first two years were contentious, and Michael didn’t help matters by terminating a well-liked office secretary for poor performance.

But there were good people as well as a few turkeys and with the addition of many newcomers, the old guard’s influence was diluted somewhat. With consistent preaching, a more than adequate music program, and attractive religious education classes for children and adults, the auditorium began to fill up on Sundays and money ceased to be a problem. During the waning years of the Cold War, Michael and several supporters brought the church into the nationwide Sister City Pairing Project. This initiative linked U.S. cities with their Soviet counterparts (Borovichi, in our case), and soon letters were being exchanged and plans made for the exchange of delegations. The program raised the profile of Binghamton’s Unitarian Universalist church significantly. Michael, by now a familiar figure in the local running community, then proposed a church-sponsored eight kilometer road race through the neighborhood (the Peace Run) which would double as a fund raiser for the Pairing Project. Michael stayed long enough to direct three of these August races. He continued to enjoy success in his own running, and was named the Triple Cities Runner of the Year for his performance in a series of four races of varying distance. During his years in Binghamton, Michael ran ten marathons (with a personal best time of 2’36”), including five in the granddaddy of all races, the Boston Marathon.

But success led to conflict with several of the church’s board members, and since Trina had now given birth to Kyle, her and Michael’s first and only child, it made sense to find a community where a young family could settle in for the long haul. Michael sent his professional resume to larger congregations in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Portland, Maine, Columbus, Ohio, and Madison, Wisconsin. Three of the four asked him to be their candidate, but Madison was the clear choice. With an “Escape to Wisconsin” bumper sticker on the back of their Ford Taurus, in the sweltering heat of July 1988 the humans and their five-year old Lhasa Apso (Jhana) headed for the Dairy State.

Michael’s immediate predecessor, The Rev. Max Gaebler, had retired in 1987 after thirty five years of service to the Madison congregation. Max had spent the interim year in Australia and New Zealand, but was back home when his successor arrived on the scene. Michael and Max had already agreed to a covenant crafted by a church committee, which laid the groundwork for mutually rewarding, collaborative relationship for the next decade. First Unitarian Society experienced stunning growth during that period as the result of several interlocking factors: the best church music program in Madison, a unique religious education program for children, a fresh, young voice in the pulpit, and the ongoing presence of a very popular former minister in the life of the congregation.

As Michael’s responsibilities increased, competitive running became a luxury he could no longer afford; it became instead a daily discipline he depended upon to maintain physical fitness, emotional stability, and mental sharpness. Michael had long wanted to practice some form of movement meditation, and under the tutelage of a local expert, mastered a version of the tai chi Yang form after two years of practice. He also became adept at several types of Qi Gong, which he then proceeded to share with members of the congregation. By the end of his first decade in Madison, Michael was composing regular monthly columns for a local newspaper, “The Capitol Times,” and essays he’d been commissioned to write found their way into several books published through the Unitarian Universalist Association, as well as other periodicals. No doubt, Michael’s work exacted a toll on his family life, but he, Trina and Kyle did enjoy long trips to Yellowstone National Park, the Smokey Mountains, and California. Michael also volunteered at Kyle’s school and served as “Pack-Master” for his Cub Scout Troop.

Following a pattern established by his predecessor, Michael became involved with UW-Madison campus life, serving on the advisory board for the undergraduate honors program, and as the community representative on the All-Campus Human Subjects Committee. He presided at memorial services for many distinguished faculty members and worked to strengthen the near-moribund Unitarian Universalist student organization on campus. In the larger community, Michael served on the regional Planned Parenthood advisory board and as a member of the Interfaith Coalition for Worker Justice board. He was also voted into the prestigious Madison Literary Club, one of the oldest academically focused organizations in the community.

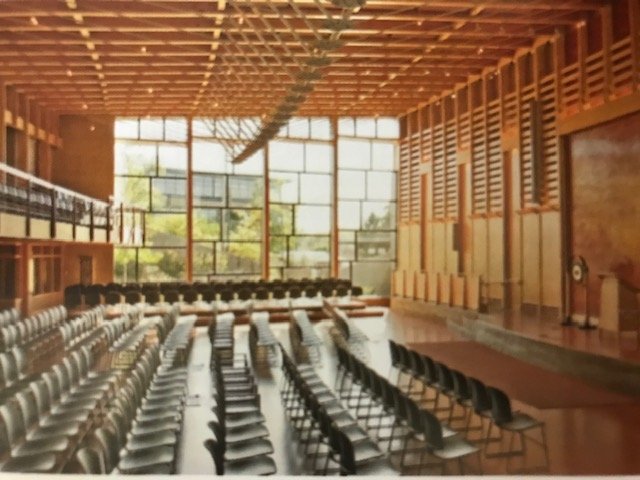

Congregational growth was accompanied by the need for expansion. The First Unitarian Society had already spun off two other UU congregations, on the Southside in 1969 and Eastside in 1995. But by 2005 it became clear that the congregation had again outgrown the historic, National Landmark Frank Lloyd Wright Meeting House that had served as its home since 1951 (an interesting aside: the first worship service to be held in that building occurred on February 4, 1951 - three days before Michael’s birth). After a lengthy study and spirited debate, the congregation voted overwhelmingly on a major addition with a second, much larger auditorium, new meeting spaces, a library, institutional kitchen, and a Commons large enough for social gatherings. The congregation also prioritized an environmentally responsible “green” structure and, despite the price tag, included in the plans a “living roof,” geothermal heating and cooling, and other energy and water-saving features. The “Atrium Addition” earned a gold-level LEED certification, which at the time made it the most eco-friendly faith-based building in Wisconsin. Within the first year, it has garnered several national and regional architectural awards.

The new Atrium Addition was completed just as the Great Recession of 2007-2008 hit, and because of significant cost overruns during construction, the congregation - despite a capital campaign that had raised $6.5 million dollars - was saddled with a sizable mortgage. Like many other churches, FUS was hit hard by the recession; giving declined, then rebounded, but growth slowed as families struggled with their own finances. Nevertheless, attendance during those perilous times held steady and even increased, and when the opportunity to refinance under more favorable terms presented itself, a mortgage crisis was averted. During his last decade at FUS, Michael continued to enjoy success as a writer, with publication of “Making the Good Life Last,” and as a speaker, with multiple engagements throughout the community and in the larger Unitarian Universalist world. In 2011 he was invited to deliver the sermon at the Service of the Living Tradition, an historic event held each year during the General Assembly of UU Congregations. Over four thousand delegates in Charlotte, North Carolina, heard him speak on the crisis of authority facing today’s clergy. Michael entitled his discourse“The Face of God or a Face in the Crowd?”

Retirement in June of 2018 didn’t come a day too soon. By March, Michael’s 96 year-old father was experiencing a rapid decline, both mentally and physically. As his Power of Attorney, Michael was tasked with managing the older man’s personal and financial affairs, and after he passed away, putting those affairs “in order,” as they say. Charles’ living quarters (he and Nancy were living apart at that point) were in a state of complete disarray and he had been drawing down his resources at a rapid clip. It would be six months before Michael had brought some semblance of order to the situation. Meanwhile, Nancy’s medical needs increased and Michael became a part-time care-giver and bookkeeper. The release from professional responsibilities was a godsend, and also provided Michael with the opportunity to do some serious writing. Two book projects now claimed his attention: an interdisciplinary critique of humanism and a memoir focused on his father. The 275 page study Humanism: In Command or in Crisis is now available through his publisher, Wipf and Stock, on Amazon, or directly from the author (michael@maschuler.com)